To return, or not to return: LPDP’s necessary quest for a better Theory of Change

The program needs to rethink its design for better impact

It’s hard to imagine a time when LPDP, Indonesia’s government funded postgraduate scholarship, isn’t a household term; today’s internet is awash with both positive and negative coverage of the program as well as its alumni.

On paper, the purpose of LPDP is benevolent: it dreams to increase Indonesia’s human resource capacity, advancing skill sets of young Indonesians to fulfill national development goals. Almost fourteen years since its inception, the scholarship has awarded 45,577 students.

LPDP was first introduced by Minister of Finance Sri Mulyani in 2010 to fulfill the mandate of our Constitution: at least 20% of the national budget (APBN) has to be allocated towards education. She observed that despite the allocation, this budget was often under-utilized.

Upon finding out that her Malaysian and Singaporean counterparts have internationally-educated employees, she too sought to create an endowment fund that provides a structured approach to facilitating higher education abroad for local talents.

But the general public is questioning its impact:

Spending IDR 5-29 trillion per year to help privileged kids get MBAs abroad? Why not fund those from poor families who couldn’t afford to go to university, or severely underpaid teachers, instead?

The leaders are listening. Stella Christie, the new Deputy Higher Education, Research, and Technology Minister, said she is spearheading a cost-benefit analysis on LPDP’s impact, questioning whether allocating a huge portion of the budget sponsoring masters degrees has been optimal. Meanwhile, Finance Minister Sri Mulyani said she and her deputy Suahasil Nazara met with McKinsey to talk about reforming the way LPDP is being managed.

We at The Reformist—some direct beneficiaries of LPDP—had our fair share of intense internal debates on how the program can improve. And we conclude that there is a reason why the program, while well-intentioned, is always under public scrutiny: LPDP does not have a robust Theory of Change.

In this edition, we want to argue our take on the four reforms through which LPDP could rethink its ToC.

First, the government should orient LPDP based on a mapping of the country’s human resource gap. Utilize existing data (e.g. critical occupations list) to inform program priorities.

Second, improve LPDP’s mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation, ensuring alignment with Indonesia’s needs. Analyze and publish what kind of data can be collected from alumni and how that would inform the program’s implementation.

Third, alumni need to be better-incentivized to return, or better-disincentivized to stay away. Explore forgivable loans, dual-approach scholarships, and pre-approved working pathways.

And lastly, consider alternatives to the required time of return (2N+1) and establish better employment support for awardees once they do return.

Chapter 1: LPDP’s urgent need for a crystal clear Theory of Change

Inherently, scholarships for higher education are regressive. Think about it this way: if a student has already achieved an undergraduate degree and received an acceptance for their higher education, it is highly likely they have somewhat advantageous backgrounds, whether that comes in the form of wealth, connections, or location.

But it is not necessarily a bad thing; it simply means that LPDP fundamentally serves a different primary purpose than equity. Among others, it has the potential to address Indonesia’s ‘middle income trap’, close the higher-skill gap amongst Indonesia’s human capital, or create a new cohort of policy and economic leaders generating new opportunities and breaking ceilings.

Still, its inherent risk of perpetuating educational inequity needs to be mitigated. Indonesia’s gross enrollment rate (GER) in higher education for the poorest quintile sat at only 15.96% in 2021, compared to 55.67% for the wealthiest. Affirmative scholarships targeting underprivileged areas is a way to mitigate this, albeit Javanese and urban applicants remain overrepresented.

Simply put, when LPDP claims that the program is supposed to improve overall development and upskill the labor force, it will likely fail without substantial mechanisms to create change beyond existing structures of privilege to create unprecedented labor advancement.

This is not to say that the program has not succeeded in creating a pool of highly-skilled professionals; it only means that a specific design is needed to ensure a fair ‘return’ or multiplier impact so long-term benefits are not disproportionately enjoyed by those who are already well-positioned to succeed.

Ultimately, this won’t be achieved without a robust theory of change driving LPDP’s design and implementation mechanisms:

#1 Orient the scholarship based on a robust analysis on Indonesia’s human capital gap

On its website, LPDP states that they seek to develop the Indonesian labor force in fields that “support the acceleration of development” in Indonesia, which includes engineering, science, agriculture, law economics, finance, medicine, religion, and socio-cultural studies.

Not only are these broad fields, there is also little in-depth explanation as to why these fields are so crucial, and where alumni are expected to apply this knowledge.

A 2018 study by the World Bank and the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs compiled a critical occupations list (COL) which identified positions that (1) faced labor shortage, and (2) strategically benefited the country.

Of the nine groups they identified, eight required at least a secondary education. These occupations included positions ranging from trade workers to machine operators, agricultural workers, and technical professionals.

While the wide-ranging net of academic pursuits that LPDP casts may be beneficial independently, the lack of precision and alignment with broader state goals render it impractical. Alumni who major in particular fields may not necessarily work in that field, and so fail to contribute to addressing critical skill gaps in the labor market.

Explicitly aligning funding priorities with real-time labor market needs—as well as correctly predicting labor market needs—would make the LPDP program far more effective.

There are signs that this may move forward incrementally in the coming years. In the 2023 LPDP Annual Report, the LPDP showed signs of shifting the focus of study areas.

The characterization of “incrementally” is because there is little else other than a shift in majors to encourage LPDP applicants. At the moment, the breakdown is 48% STEM and 52% non-STEM. Now, the program seeks to cause the proportion to be 70% STEM and 30% non-STEM.

The problem with this is two-fold.

First, there is no guarantee that increasing the proportion of STEM graduates will directly translate into developmental impact, particularly considering job opportunities and their regional distribution.

The success of such a shift depends on whether these graduates are funneled into sectors critical to national development, such as renewable energy, technology, or infrastructure. Without a robust linkage between STEM-focused scholarships and corresponding job markets or national priorities, the program risks producing a surplus of graduates in fields that may not align with labor market demands or regional needs.

Second, the overt focus on STEM may backfire if it leads to poor governance.

Humanities graduates contribute critical skills in policy-making, ethical reasoning, cultural understanding, and communication. These skills are essential for addressing complex social challenges in Indonesia.

For instance, crafting inclusive policies, managing diverse populations, and upholding democratic values require insights and competencies often derived from fields like political science, sociology, and law.

Thus, the importance of labor upskilling extends beyond academia. Critical supporting infrastructure, such as practical training and job opportunities, is crucial for employment.

As part of setting clear goals for LPDP alumni aligned with the COL, the government should recognize comprehensive approaches to building opportunities for vocational training, apprenticeships, and partnerships with industries to ensure that graduates are equipped with not only theoretical knowledge but also the hands-on skills required in the workforce.

#2: Improve monitoring, evaluation, and learning mechanisms

LPDP frequently claims significant positive impact on Indonesia through facilitating the education of future leaders, given the potential for those individuals to influence the state’s diplomacy, trade partnerships, and military agenda.

Although alumni are intermittently asked to provide updates on their place of work, public data on alumni results is limited at best and completely non-existent at worst. The lack of tracer studies and alumni tracking means that it is challenging to assess the full impact of the LPDP program on Indonesia's development.

Beyond incessantly citing lists of famous alumni, LPDP as a whole has done little to empirically prove this. There is no causal link between receiving an LDPD scholarship and influencing national development.

After all, if many of these individuals were externally predisposed (supported by preparatory courses, extracurriculars) to be accepted into elite universities, were they not perhaps externally predisposed to influence national development? How big is the impact of LPDP in comparison to other factors, and what did LPDP contribute that makes it pivotally different from other opportunities the same individual may receive?

Tangentially, the correlation between LPDP and the sector(s) which LPDP alumni work in is difficult to measure.

There is an absence of structured data on where and how alumni contribute post-graduation. As noted in the section above, the LPDP currently lacks specific targets for alumni contributions by profession or industry, leaving their impact largely anecdotal.

In fact, 2023 was the first year that LPDP Annual Reports included a breakdown of alumni results—albeit briefly. In previous years, this portion of the report had been filled with a list of around ten standout alumni, highlighting their career paths as representative of the LPDP program’s success, with limited empirical data.

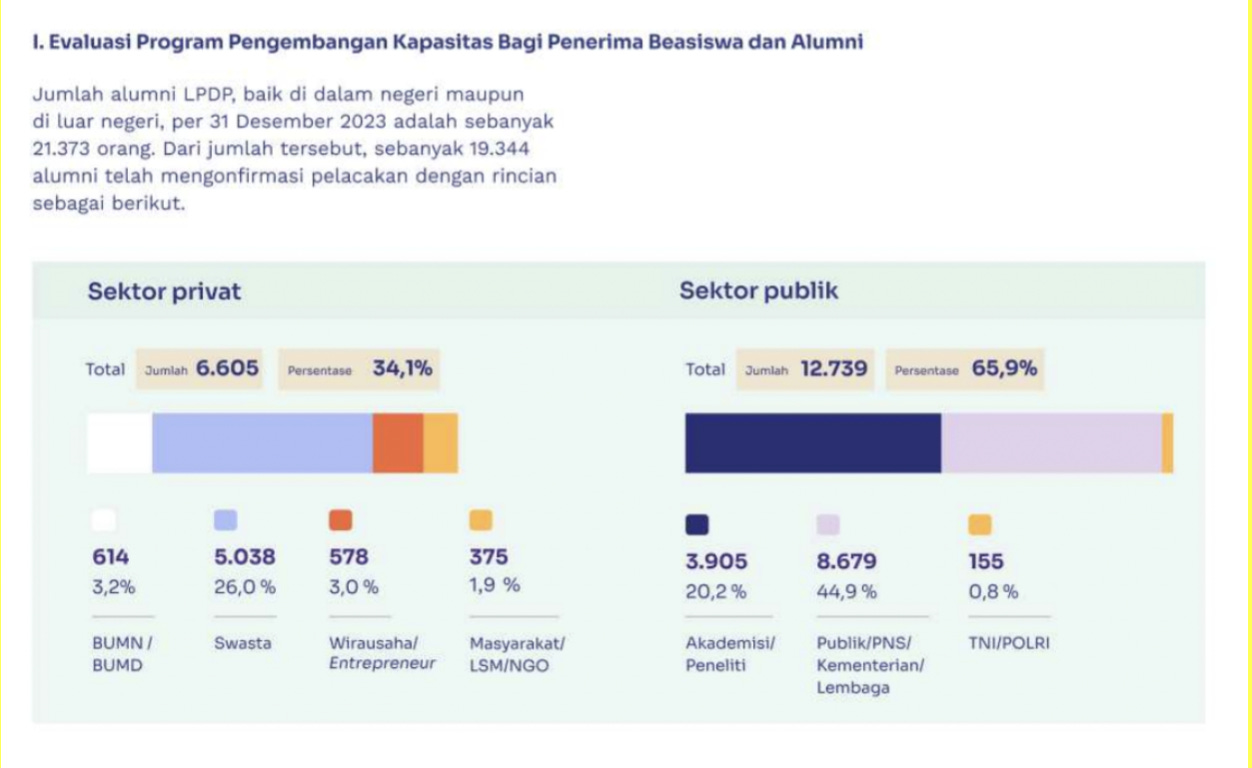

The 2023 report stated that, as of December 2023, alumni of the program amounted to 21,373 individuals, 19,344 of whom were included in the following breakdown:

It’s difficult to analyze the data when it is limited and lacking in previous comparisons, but the majority (65.9%) of LPDP alumni working in the public sector as opposed to the private sector should be a comfort to some.

Although the inclusion of this data is an assuring step in the right direction for monitoring and evaluating the program, it remains insufficient for linking the LPDP to driving national development.

After all, these numbers only initiate more questions: what industries are popular for alumni to work in? Do they align with the previously-stated goals of state development? What kinds of entrepreneurships, and what legitimizes an entrepreneurship?

Radically, to ensure that LPDP alumni contribute to Indonesia’s development, the government could introduce a system of pre-approved places of work and study, aligning career pathways with national priorities.

Private companies, BUMN, and government agencies could propose job slots for LPDP alumni after demonstrating how these roles support key development goals.

By linking LPDP alumni to critical sectors like education, health, and technology, this approach would encourage graduates to work in fields that directly benefit the nation, rather than solely pursuing personal financial gain. This system would ensure LPDP funding generates a tangible return on investment for the country’s growth and development.

Regardless, without specific metrics or case studies to back these figures, it is challenging to measure the program's success beyond superficial numbers.

To effectively link LPDP's outcomes to national development, a more comprehensive evaluation framework is needed. This framework should include clear metrics for industry alignment, role significance, and entrepreneurial impact.

Considering LPDP is run with the explicit goal of elevating human resources to push state development, it would be beneficial for the government to apply better mechanisms for tracking the correlation between LPDP, state development, and student achievement.

Some examples of these may include:

Trace studies to track career paths of alumni over decades, based on consistent key point indicators.

Mechanisms that report on how alumni study and career align with local/regional/state developmental goals.

Impact reports that correlate alumni initiatives with state and regional development indicators,

Establishing a feedback framework where alumni experiences inform program improvements.

Chapter 2: Should awardees return?

A key part of the LPDP program is that awardees are contractually obligated to return to Indonesia, barring some circumstances, such as continued study or job postings deemed to be beneficial to the state, where they must work for twice the study period plus one year (2n+1).

However, hundreds of alumni failed to return home. As reported by Narasi last year, 413 of 35,536 alumni that year had not returned to Indonesia. This number counts those who have been approved to stay abroad, but the proportion is unclear.

Considering the fact that LPDP has already cost a staggering $962 million this year alone, the issue of awardees not returning to Indonesia has been the subject of frequent controversy.

According to LPDP President Director Andin Hadiyanto, this is due to several reasons, including alumni marrying foreigners, seeking jobs with higher pay, and preferring to pay back the state rather than return.

How can LPDP tackle the issue of alumni not returning to Indonesia?

#3: Consider forgivable loan and dual-approach scholarships

The option to repay the scholarship instead of returning undermines the program’s core goal of fostering national development.

For alumni in high-income fields, the financial penalties for staying abroad are not a frequent deterrent. This creates a loophole where alumni with lucrative opportunities abroad may stay abroad rather than fulfill the contractual obligation.

In this sense, while there is a financial penalty for LPDP awardees who do not return, breaking the contract has not been fully disincentivized.

While some individuals might genuinely expand their potential by pursuing opportunities overseas, it raises a fundamental question: should taxpayers fully fund their education when their work does not align with advancing Indonesia’s national development?

A feasible approach could be the adoption of forgivable loans to ensure alumni accountability while effectively upholding the program’s purpose of contributing to Indonesia's national development.

A forgivable loan is a form of loan which can be forgiven or deferred for a period of time by the lender (in this case, LPDP) when pre-approved conditions are met. It is more like a grant with conditions rather than a loan, as in most cases the loan is forgiven if all the conditions are met.

However, if the conditions are not met the loan has to be repaid, usually with interest, thus incentivizing the previously-mentioned condition (namely, returning and contributing to Indonesia’s development).

The application of a forgivable loan for scholarships is not unprecedented, albeit perhaps in different contexts. The US’ Federal TEACH Grant obligates recipients to teach at a low-income school for at least four years within eight years of graduation. If they fail to do so, they convert to a Federal Direct Unsubsidized Loan, which must be repaid with interest.

Alternatively, Japan’s flagship program (JASSO) offers both grant-type and loan-type scholarships, meaning that some are completely free, and others are established as loans from the beginning.

This dual-approach model is particularly viable, because it would allow LPDP to balance its mission of national development with the practical realities of alumni career trajectories. Moreover, it could help the program become more financially sustainable by allocating resources strategically based on the likelihood of returns—whether financial or developmental.

#4: Reconsider 2n+1 and establish better employment support for awardees

As mentioned briefly above, the US’ TEACH grant includes the option that allows students to stay abroad, as long as they come back within a given number of years.

This way, there is an opportunity for students to both work abroad and gain vocational skills on an international level, before returning to fulfill their obligation. This would be a two-prong solution, considering the intriguing issue of LPDP scholarship recipients who struggle to find employment in Indonesia that aligns with the skills they gained abroad.

Although awardees staying abroad may arguably undermine the program’s goals, one must also wonder whether the lack of equitable and fair employment infrastructure (pay, conditions, sectors, etc) on part of the state equally undermine the LPDP program.

Perhaps, future reforms must focus on creating strategic partnerships between LPDP, the central government, and leading industries to better-integrate LPDP alumni into high-impact roles.

Alternatively, subsidizing pay for LPDP graduates is a potential step to address disparities in employment opportunities for highly skilled graduates. LPDP alumni could be provided with subsidized salaries to work in sectors critical to Indonesia’s development, such as renewable energy, technology, or education.

Such a scheme would ensure alumni remain motivated to return while addressing gaps in the domestic labor market's ability to absorb advanced expertise. This model can be used to effectively support researchers by ensuring competitive compensation in the local market. If the state wants to increase LPDP alumni in the public sector, this offers a feasible alternative. Although, it would require significantly more investment into the program.

Conclusion

The LPDP program is an incredible way to equip Indonesia with the skills, infrastructure, and knowledge for the country’s long voyage ahead. However, cracks in its design risks undermining its mission and the country’s wellbeing as a whole.

Without reforming the way it thinks about its theory of change, (our recommendation being to map critical labor needs, utilize alumni outcomes, and provide incentives for meaningful return) the program risks being squandered.

To ensure that LPDP truly helps Indonesia realize its ambition, reforms must align its course with Indonesia’s developmental priorities, strengthening its human resource capacity and ensuring that no one is left behind. By reforming its approach, the LPDP can be far more effective to steer Indonesia confidently through uncharted waters.

—